Assault Weapon Truth

The Facts Buried Beneath the Rhetoric about “Assault Weapons”

What is an “assault weapon”?

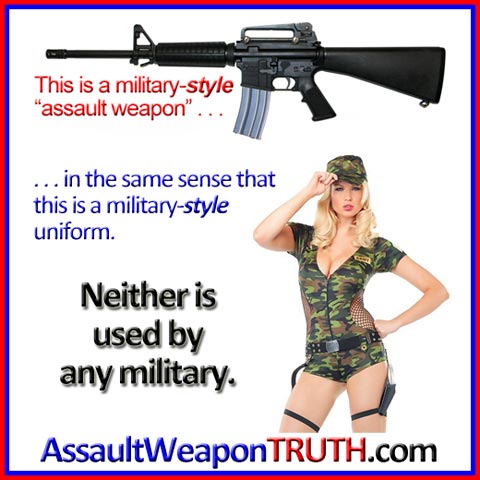

As used by the media, politicians, and gun control activists, “assault weapon” is a loosely defined term for a semiautomatic civilian firearm that has the appearance—but not the function—of a fully automatic military firearm. Because these guns have the appearance of military firearms but are not actually used in military operations, they are sometimes referred to as “military-style assault weapons.”

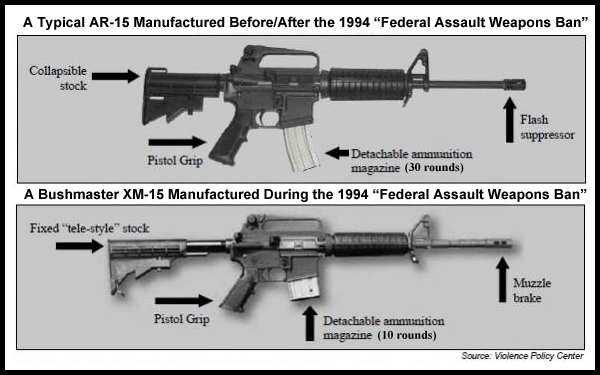

The 1994 U.S. “Federal Assault Weapons Ban,” which expired in 2004, defined a rifle as an “assault weapon” if, in addition to being semiautomatic, it could accept a detachable magazine and had at least two military-style features such as a folding or telescoping stock, a pistol grip, a bayonet mount, a flash suppressor, or a threaded barrel designed to accept a flash suppressor. (The list of military-style accessories also included “a grenade launcher”; however, grenade launchers and grenades were already restricted under federal law; therefore, this provision primarily applied to a type of inert barrel bushing.) Although most of the affected weapons were rifles, there were separate criteria under which a pistol or shotgun could be classified as an “assault weapon.”

It is debated whether the term “assault weapon,” which entered the American lexicon in the late 1980s, originated as a political ploy by gun control advocates or as a marketing ploy by gun retailers. What is certain is that “assault weapon” is not a technical term, a term of art used by firearm manufactures, or a military term. The closest match in any of those categories is the term “assault rifle,” which is a military term referring to a shoulder-fired rifle that fires an intermediate (i.e., medium-powered) cartridge and allows the shooter to select between semiautomatic mode (the gun fires one bullet per pull of the trigger) and either fully automatic mode (the gun continues to fire bullet after bullet for as long as the trigger is depressed) or burst mode (the gun fires a predetermined number of bullets per pull of the trigger).

Because “assault weapons,” as defined by state and federal law, are semiautomatic only and can fire in neither fully automatic mode nor burst mode, they are not assault rifles. (THIS article explains the current United States laws restricting civilian ownership of fully automatic/burst-fire firearms—aka machine guns—and explains why those weapons are not part of the ongoing debate over gun control in America.)

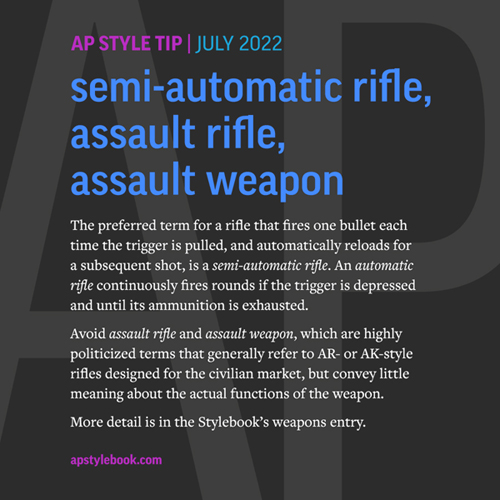

Unfortunately, despite “assault weapon” and “assault rifle” being clearly defined in the Associated Press Stylebook (prior to 2013, the AP’s definition of “assault weapon” even included the warning “Not synonymous with assault rifle, which can be used in fully automatic mode”), the media often conflates these two similar-sounding phrases—using “assault rifle” when they mean “assault weapon”—thereby further confusing the public on the relationship between so-called “assault weapons” and true weapons of war.

None of the assault rifles found on the battlefields of Afghanistan, Iraq, or Vietnam are available for sale in American sporting goods stores. In fact, of all the guns for sale at your local sporting goods store, the three most likely to have been found on any of those battlefields are the Remington 700 bolt-action hunting rifle (used by U.S. snipers since the 1960s), the Colt M1911 pistol (used by U.S. troops since the early 1900s), and the Beretta M9 pistol (used by U.S. troops since the 1980s).

A 2020 update to the AP Stylebook recommends against using either “assault weapon” or “assault rifle” to describe a semiautomatic firearm, because the terms “convey little meaning about the actual functions of the weapon.”

In the aftermath of the October 1, 2017, Las Vegas shooting (the worst mass shooting in U.S. history), the debate over “bump stocks,” which turn a semiautomatic rifle into a pseudo-automatic rifle capable of closely matching the rate of fire of a fully automatic firearm, clearly illustrates the difference in lethality between semiautomatic and fully automatic fire. An analysis by The New York Times compared a short audio clip of a fully automatic rifle at a firing range with short clips from the Las Vegas shooting and the June 12, 2016, shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida.

Over seven seconds, the fully automatic rifle maintained a rate of fire of 14 rounds per second. Over 10 seconds, the Las Vegas shooter’s pseudo-automatic rifle maintained a rate of fire of nine rounds per second. Over nine seconds, the Orlando shooter’s semiautomatic rifle maintained a rate of fire of 2.7 rounds per second, an exceptionally fast rate of fire for a semiautomatic rifle but still only one-third the rate of the pseudo-automatic rifle and one-fifth the rate of the fully automatic rifle. (For comparison, HERE is video of a Canadian cowboy-action shooter using firearm models from the late 1800s—a lever-action rifle, two single-action revolvers, and a pump-action shotgun—to accurately fire 24 rounds in under 11 seconds, a rate of fire of 2.2 rounds per second.)

Although some journalists and proponents of banning “assault weapons” are quick to point out that U.S. soldiers are trained to fire their assault rifles in semiautomatic mode under most circumstances, the capability to switch to burst or fully automatic fire when extreme force is needed is the defining characteristic of an assault rifle. That characteristic is what differentiated the German Sturmgewehr, the first assault rifle, from the rifles that came before it.

The exceptional lethality of fully automatic firearms is the reason the U.S. has heavily regulated such weapons since 1934. Without the capacity to fire multiple rounds per pull of the trigger, there is little functional difference between a military-style “assault weapon” and a semiautomatic hunting rifle, a semiautomatic handgun, or even a revolver—all have the same rate of fire (one round per pull of the trigger).

It’s important to understand that although the rate of fire can vary between different models of machine guns (aka fully automatic firearms), no semiautomatic firearm has a faster rate of fire than any other semiautomatic firearm.

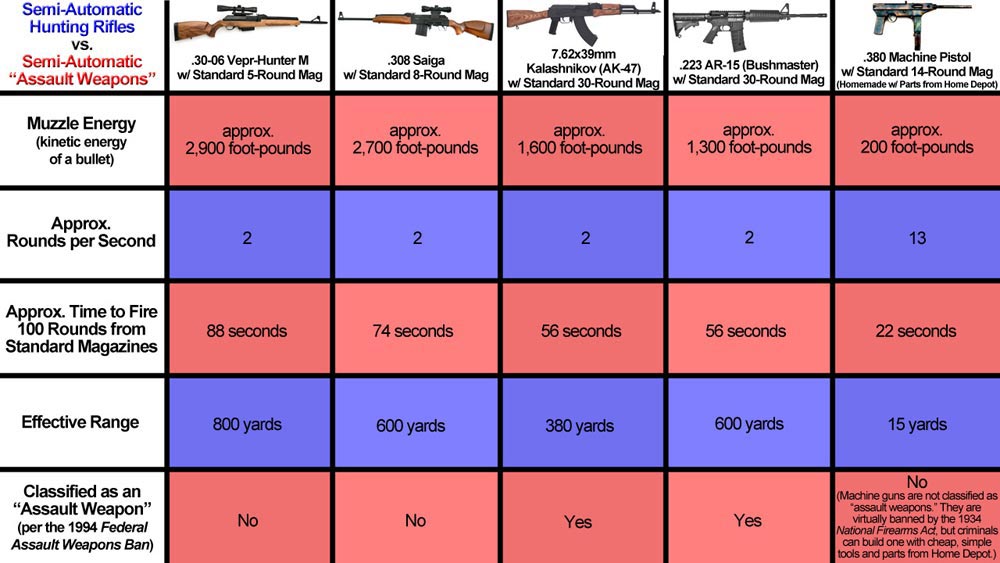

This chart compares the lethal qualities of a semiautomatic AK-47 “assault weapon” and a semiautomatic Saiga .308 hunting rifle.

This 11-minute video addresses some of the public confusion over “assault weapons”:

Further confusing the issue is the fact that well-respected members of the news media often get the facts very wrong when reporting on “assault weapons.”

In this now-infamous 2003 CNN segment about the then-pending expiration of the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban,” a CNN reporter identifies an AK-47 held by a police detective as “one of the banned weapons—the nineteen currently banned weapons” and then has the detective demonstrate the destructive force of the firearm by firing it in fully automatic mode (a mode not featured on any of the 19 weapons banned under the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban”):

In this live segment from that same day, the detective demonstrates two firearms—one banned and one not—but switches targets after firing the banned gun, before firing the unbanned gun. The camera remains fixed on the first target, inadvertently creating the impression that only the banned gun was capable of penetrating the cinder block targets (even though both guns fire the same ammunition at the same velocity and have the same rate of fire):

This segment makes a point of showing that rounds fired from the banned rifle can penetrate a bulletproof vest, despite the fact that both rifles (which fire identical ammunition) are equally capable (as is any hunting rifle) of penetrating the same bulletproof vest.

In this August 20, 2014, CNN panel discussion on the then-ongoing civil unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, anchor Don Lemon claims that he was able to buy an “automatic weapon” in Colorado and that the whole process only took 20 minutes. When guest Ben Ferguson corrects him by pointing out that Lemon actually purchased a semiautomatic weapon, Lemon refuses to acknowledge the difference:

In the same way that a semicircle is not a circle, a semiautomatic rifle is not an automatic rifle.

In this December 4, 2015, Fox News segment on the December 2 massacre of 14 persons in San Bernardino, California, reporter Greg Jarrett claims that a bullet button—a device that turns a detachable magazine into an integral magazine, to comply with California’s “assault weapons” ban—is actually a button that “turns your legal semiautomatic weapon into an illegal [fully automatic] weapon”:

It’s true that California law allows possession of some semiautomatic rifles; however, under the version of California’s “assault weapons” ban in effect in 2015, semiautomatic AR-15 rifles like the ones used by the San Bernardino shooters were illegal unless the gun’s magazine was affixed via a bullet button or similar device (California has since banned bullet buttons). Contrary to Jarrett’s claim, an “assault weapon” is not fully automatic and does not “continue to fire when the trigger is pressed.” At various points during this discussion, Jarrett uses the terms “assault rifle” and “assault weapon” interchangeably. Most egregiously, Jarrett claims that a bullet button (so named because the tip of a bullet can be inserted into the device to remove the magazine from the weapon) is actually a device that, through some sort of legal loophole, allows a semiautomatic rifle to be turned into a fully automatic machine gun with the press of a button.

In this June 14, 2017, NBC News segment about that day’s shooting attack on a congressional baseball practice, former Secret Service agent Evy Poumpouras states, “So the difference is a pistol can fire one round at a time—POP . . . POP . . . POP—which is what the Capitol Police were carrying. This individual had a rifle. ‘Semiautomatic’ means that you can switch it to a point where it fires POPPOPPOP—multiple rounds”:

In reality, semiautomatic firearms do not have a switch that allows them to fire faster or slower. They have only one firing mode—they fire one round each time the trigger is pulled. As with virtually all U.S. law enforcement agencies, the pistols carried by the Capitol Police are semiautomatic and have the same rate of fire as a semiautomatic rifle or any other semiautomatic firearm.

In a May 18, 2018, article in USA Today, about that day’s mass shooting in which a gunman used a shotgun and a revolver to kill 10 people and injure 13 others at Santa Fe High School in Santa Fe, Texas, reporter Christal Hayes writes, “The guns may have slowed down the gunman’s deadly rampage because they have a slower firing rate than firearms used in other recent mass shootings, such as the AR-15…High-powered rifles such as the AR-15 can be fired more than twice as fast as most handguns.”

In reality, most handguns (both semiautomatics and revolvers) fire as rapidly as the shooter pulls the trigger—no faster or slower—just like an AR-15. There is no factual basis for asserting that an AR-15 “can be fired more than twice as fast.”

What about the claim that a pistol grip coupled with the relatively low recoil of an “assault weapon” makes it easier to “spray fire” these weapons?

On a semiautomatic firearm, a pistol grip simply makes the gun more ergonomic, and low recoil simply makes the gun more comfortable to shoot. No semiautomatic firearm is any better suited for “spray firing” than any other

Pistol grips and low recoil improve accuracy during fully automatic fire because they help prevent muzzle climb; however, those features have little impact on semiautomatic fire because the muzzle of the gun has enough time between shots (it only needs a fraction of a second) to fall back into line with the target. Even with a fully automatic rifle, those features wouldn’t be a major factor in a mass-shooting scenario because accuracy is not a significant concern at short distances. If your target is 10 feet away, your muzzle can climb six inches and still be on target.

Aren’t the high-powered rounds fired by “assault weapons” capable of penetrating police body armor?

The soft body armor (Type I – IIIA) worn by police officers is designed to stop handgun fire, not rifle fire. Any centerfire rifle ammunition is capable of penetrating police body armor.

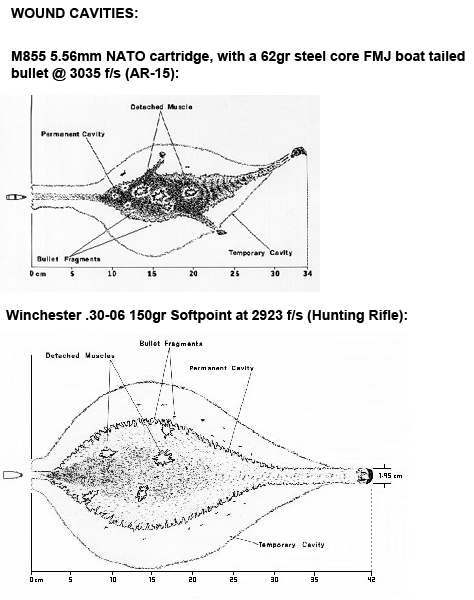

The most common “assault weapon” rounds are significantly less powerful than the most common hunting-rifle rounds.

The 5.56×45 and the .223 are essentially the same round; therefore, the two names are used interchangeably.

Some opponents of “assault weapons” argue that, because the high-speed 5.56/.223 round fired by most AR-15s is extremely damaging to living tissue, the AR-15 is an unusually dangerous firearm that should not be available to the average citizen. This ignores the fact that the AR-15 is a modular system that can be configured to accept any of a multitude of calibers.

Because the argument about 5.56/.223 rounds being too fast cannot be made about other AR-15-adaptable rounds such as the .300 BLK and the 7.62×39 (a round popularized by the infamous AK-47), it would make more sense for gun control activists to seek a ban on the 5.56/.223 cartridge, not the AR-15 rifle (which is one of numerous firearms—not all of which are considered “assault weapons”—capable of firing the 5.56/.223).

The most likely reason gun control activists hesitate to seek a ban on 5.56/.223 ammunition is that the same characteristics that make the 5.56/.223 round so devastating also make most hunting rounds equally devastating if not more so. Compared to the 5.56/.223, the ubiquitous .308 Winchester hunting cartridge projects a bullet that is 40% wider and more than twice as heavy, at a comparable rate of speed, resulting in much higher kinetic energy. The .22-250 Remington hunting cartridge has the same size bullet as a 5.56/.223 but a much larger powder load, resulting in a round that travels as much as 1,400 feet per second faster than the 5.56/.223.

The .30-06 Springfield cartridge projects a bullet that has up to three times the kinetic energy of a 5.56/.223 round.

The .308 Winchester has an effective range of 800-900 meters, a good 200-300 meters farther than the maximum effective range of the 5.56/.223 and a good 500-750 meters beyond the point at which 5.56/.223 ammunition shows significantly degraded performance.

The bolt-action M24 and M40 sniper rifles used by the U.S. military are accurized Remington 700 hunting rifles chambered in either .308 or .338 Lapua Magnum. The military’s M21 and M25 are semiautomatic sniper rifles chambered in .308. Neither was banned by the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban.”

An August 2, 2018, article from Omaha Outdoors dissects an NPR video that emphasizes that a .223 round is much more devastating than either a 9mm handgun round or a small rimfire round like the .22 Long Rifle. The video misleadingly refers to the .22 LR as a “common hunting round,” despite the fact that the .22 LR is only commonly used to hunt small game such as squirrels and rabbits. The video completely ignores the existence of all rounds commonly used to hunt medium and large game (e.g., deer, elk, and moose).

The Omaha Outdoors article explains:

Yes, 223 is more “devastating” than 9mm in soft tissue – but common hunting rounds like 30-06, 270 Winchester, and 300 Win Mag are far more “devastating” than 223. The average person would not know that from watching this video – they would be left with the thought that the 223 is exceptionally devastating in comparison with a “common hunting round,” the 22LR. They wouldn’t know that cartridges used for hunting larger animals look far more ‘devastating’ in ballistics gel. After watching this NPR video, the average person wouldn’t know that common centerfire cartridges even exist.

A September 11, 2018, article in Scientific American, about a recent Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) research study on active shooters, notes:

When people were injured with semiautomatic firearms as compared with other types of guns, however, it appeared the proportion of people who eventually died was roughly equal—leading to fatalities around 44 percent of the time regardless of weapon used. [Adil Haider, a trauma and critical care surgeon who directs the Center for Surgery and Public Health at BWH,] attributes the similar rate to the fact that in each of these incidents an active shooter would likely be shooting at close range in a confined space.

By claiming that the damage done by the AR-15 rifle is a result of its “military style” rather than its high-speed ammunition, gun control activists are able to perpetuate the myth that these types of injuries can be avoided by banning only firearms that serve, as they claim, “no sporting purpose.” To admit that the rifle’s design has nothing to do with the wound cavity it creates would be to admit that an effective ban would have to include not only so-called “assault weapons” but also many popular hunting rifles and calibers.

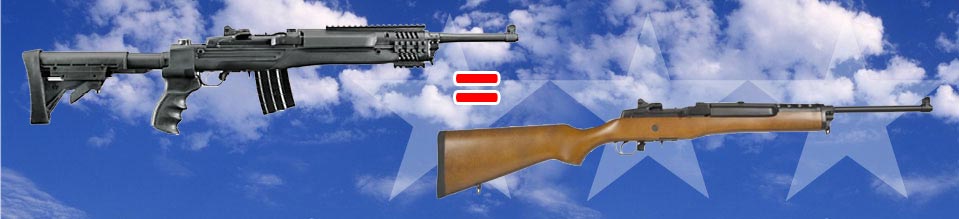

How do “assault weapons” compare to semiautomatic hunting rifles?

NOTE 1: The 5.56×45 and the .223 are essentially the same round; therefore, the two names are used interchangeably.

NOTE 2: If you doubt that a machine gun can be built with parts and tools from Home Depot, take a look at this (be advised that building a machine gun is a federal offense in the U.S).

How does a ban on “assault weapons” work?

This 6-minute video addresses the flaws inherent in the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban”:

With only two minor exceptions*, THIS is an excellent article on the current debate over whether America should pass another “assault weapons” ban.

*The article mentions that the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban” banned some weapons capable of accepting a suppressor (aka a silencer) and goes into detail about how suppressors work and why they were invented but fails to mention that since 1934, the “National Firearms Act” has required anyone wishing to purchase a suppressor to pay a $200 tax (licensing fee), pass an FBI background check (that takes about six months to complete), and either receive the written approval of his or her local chief of police (or county sheriff if living in an unincorporated area) or create a legal trust through which to purchase the silencer. The omission of these facts creates the misleading impression that suppressors were/are readily available to the general public. The article also cites a widely circulated but highly dubious statistic about Americans using firearms in self-defense more than two million times each year. This statistic is based on a 1995 phone survey of approximately five thousand respondents, conducted by criminologist Gary Kleck, a professor at Florida State University. More conservative estimates place the number somewhere between a hundred thousand and several hundred thousand.

Despite its derisive use of the word “liberal,” THIS is a very good article on the popular AR-15 (aka Bushmaster) rifle. For another perspective, THIS article, which begins, “I’m a liberal, and I own an AR-15,” is also quite good.

Was the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban” effective?

For years after the expiration of America’s “Federal Assault Weapons Ban,” which lasted from September 1994 until September 2004, the general consensus among all sides was that the ban had been a toothless, ineffective law.

In a 2003 review of the ban, the National Institute of Justice (the research branch of the U.S. Justice Department) concluded, “Should it be renewed, the ban’s effects on gun violence are likely to be small at best and perhaps too small for reliable measurement.”

A 2013 article from liberal publication Mother Jones notes:

The problems with the 1994 assault weapons ban, according to its supporters,…was that gunmakers could—and did—simply modify their semiautomatic weapons to fit the law by eliminating cosmetic features. An AR-15 without a bayonet mount is still an AR-15; it’s just marginally less effective in hand-to-hand combat with Redcoats.

The piece continues:

[Ban author] Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) promised that she and her colleagues had learned from their mistakes. “One criticism of the ’94 law was that it was a two-characteristic test that defined [an assault weapon],” Feinstein said. “And that was too easy to work around. Manufacturers could simply remove one of the characteristics, and the firearm was legal.”

In other words, even if the availability of “assault weapons” had actually represented a significant problem in the U.S., the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban” would have done little to solve that problem.

In recent years, gun control activists have tried to retroactively claim that the ban was actually effective; however, such claims are highly dubious.

Although some gun control activists like to claim that mass shootings increased by as much as 200% after the ban’s expiration, PolitiFact ranked this claim as “mostly false” because the cited analysis “[does] not adjust for population changes and [uses] irrelevant data points for comparison.” Politifact’s response also notes that “[t]rends in the incidence and severity of mass public shootings on a per capita basis also show that the rate per 100 million is similar now to that of the 1980s and early 1990s.”

Proponents of banning “assault weapons” also point to a 2017 study finding that there were fewer school shooting deaths in the years before and after the ban than during the ban; however, like the claim about mass shootings in general, this one fails to look at the types of weapons used. This study covered 10 years during which the ban was in effect and 15 years during which the ban was not in effect. During that 25-year period, the vast majority of school shooting deaths, both during and before/after the ban, were committed with handguns. Numerous others were committed with shotguns and hunting rifles. During the 10 years in which the ban was in effect, there were as many fatal school shootings involving “assault weapons” as during the 15 years in which the ban was not in effect.

THIS op-ed from the Los Angeles Times does an excellent job rebutting the recent claim that the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban” resulted in a 37% reduction in mass shooting fatalities. That claim originated in Dr. Louis Klarevas’s 2016 book Rampage Nation (which includes some other very shoddy statistical analysis of gun crimes). In short, Klarevas’s book relies on a uniquely contrived definition of “mass shooting” and willfully ignores the types of weapons used in those shootings, in order to reach a conclusion that contradicts the earlier consensus on the subject.

Here is an excerpt from the L.A. Times op-ed:

But there’s a serious flaw in Klarevas’ result: There are few actual “assault weapons” of any type in his dataset, either pre- or post-ban. Klarevas and his allies are taking an apparent drop in fatalities from what are mostly handgun shootings (again, pre-ban as well as post) and attributing this lowered body count to the 1994 legislation.

The piece continues:

I say “apparent” drop in fatalities because, as Klarevas admits in a footnote, if you use the most widely accepted threshold for categorizing a shooting as a “mass shooting” — four fatalities, as opposed to Klarevas’ higher threshold of six — the 1994 to 2004 drop in fatalities disappears entirely. Had Klarevas chosen a “mass shooting” threshold of five fatalities instead of six, then the dramatic pause he notes in mass shootings between 1994 to 1999 would disappear too.

Interestingly enough, Klarevas himself strongly condemns the methodology and findings of the only study cited in now-President Joe Biden’s August 11, 2019, op-ed calling for a renewed ban on “assault weapons.” (In this op-ed, Biden links to two separate copies of the same study, creating—either deliberately or inadvertently—the impression that he is citing multiple sources.)

Ironically, Klarevas condemns Biden’s cited study (by DiMaggio, C., Et Al.) for misclassifying unbanned guns as “assault weapons,” even though Klarevas’s own study focuses on an increase in shooting deaths predicated almost entirely on shootings with unbanned handguns.

In a January 31, 2023, column in conservative publication The Federalist, law professors E. Gregory Wallace and George A. Mocsary offer the following rebuttal to the DiMaggio study cited by President Biden:

The Violence Project publishes the most comprehensive mass-shooting database. The federal ban became effective on Sept. 24, 1994. In the preceding decade, the Violence Project database shows that 25 mass shootings resulted in 156 total fatalities. Assault weapons were used in six of those shootings with 36 fatalities. During the ban, 33 mass shootings resulted in 173 total fatalities. Assault weapons were used in seven shootings with 42 fatalities. In the post-ban decade, 46 mass shootings resulted in 328 fatalities. Assault weapons were used in eight shootings with 70 fatalities.

The Violence Project database also shows that there were more mass shooting fatalities in the decade during the federal ban (173) than in the decade before the ban (156), which contradicts the DiMaggio study’s “main message.”

Mass shootings with assault weapons also did not spike once the ban expired. Such shootings increased from six (pre-ban) to seven (during the ban) to eight (post-ban) during this 30-year period. The post-ban increase is the continuation of an existing trend.

Mass shootings and fatalities did increase in the decade following the federal ban’s expiration, but that increase is mostly from incidents involving non–assault weapons. Pre-ban, 19 mass shootings with non-assault weapons resulted in 120 fatalities. During the ban, 26 such shootings resulted in 131 fatalities. Post-ban, 38 non-assault-weapon shootings resulted in 258 fatalities.

Because there are so many varied definitions of “mass shooting,” it’s easy for activists to pick a definition that shows that there were fewer mass shootings or fewer mass-shooting deaths during the “Federal Assault Weapons Ban.” However, such cherry-picked differences are neither dramatic nor compelling.

To make the case that the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban” was effective, proponents must show that shootings decreased significantly during the time the ban was in effect and that this decrease resulted from a significant reduction in shootings with “assault weapons.” Demonstrating that there were fewer shootings with other types of weapons proves nothing, and showing that mass shootings increased after the ban expired indicates only that these types of shootings are on the rise

(NOTE: The answer to the question of whether mass shootings are on the rise depends in part on the definition of “mass shooting.” If one counts any incident in which four or more victims are hit by gunfire, mass shootings were almost certainly more prevalent during America’s violent-crime peak of the early ’90s. However, if one looks only at high-profile active shooter attacks, the number has gone up. That increase is partially attributable to America’s growing population. Researchers also note that mass shootings have a contagion effect, a phenomenon tracked as far back as the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School).

Mother Jones has identified 16 mass-casualty active-shooter attacks, with an average of 7.8 fatalities, in the 10 years prior to the ban and 15 mass-casualty active-shooter attacks, with an average of 6.1 fatalities, in the 10 years the ban was in effect. That is a negligible difference that could have been swayed one way or the other by a single shooting.

Mother Jones has identified four mass-casualty active-shooter attacks involving “assault weapons,” with an average of 7.25 fatalities, in the 10 years prior to the ban and four mass-casualty active-shooter attacks involving “assault weapons,” with an average of 7.5 fatalities, in the 10 years the ban was in effect. That suggests that the ban had no impact whatsoever on mass-casualty active-shooter attacks.

Wikipedia lists 28 mass shootings (not counting a shooting on an airliner, which downed the plane), with an average of 5.7 fatalities, in the 10 years prior to the ban, and 32 mass shootings, with an average of 4.6 fatalities, in the 10 years the ban was in effect. That too suggests that the ban had no impact whatsoever on mass shootings.

It’s worth noting that the deadliest mass shooting (not counting the shooting that downed an airliner by killing the flight crew) in the 10 years preceding the ban and the deadliest mass shooting in the 10 years following the ban’s expiration were committed with typical semiautomatic handguns, not “assault weapons.” However, the deadliest shooting during the ban involved both an “assault-style” pistol and an “assault-style” rifle.

Any credible claim that the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban” resulted in a decline in mass-shooting fatalities must account for the fact that under the ban, the firearms and magazines covered by the ban were readily and lawfully available—due to the grandfather clause that exempted previously manufactured firearms and magazines—at prices comparable to those charged before the ban. Because many manufacturers ramped up production of 30-round rifle magazines before the ban took effect, these pre-ban “high-capacity” magazines were particularly easy to come by and cost no more than before the ban.

Claims about the efficacy of the 1994 ban must also account for the fact that, as noted in the 2013 Mother Jones article cited above, slightly modified versions of the banned weapons could be lawfully manufactured and sold under the ban, at the same price point as before the ban.

In short, the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban” was a weak law that did virtually nothing to limit the manufacture and sale of semiautomatic rifles and had little impact on the supply of so-called “high-capacity” magazines.

Under the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban,” firearm manufacturers were able to manufacture and sell slightly modified versions of the guns covered by the ban. Also, firearms and magazines manufactured before the law took effect were exempt from the ban and could still be sold and traded.

What about “high-capacity” clips and magazines?

In the parlance of recreational and professional shooters, a “high-capacity” magazine is one that allows a firearm to be loaded with a greater number of cartridges than the standard capacity for that model of gun. For example, the standard capacity for an M1911 pistol is 7 rounds, so an 8-round magazine is a high-capacity magazine for an M1911. The standard capacity for a Glock 17 pistol is 17 rounds, so a 19-round magazine is a high-capacity magazine for a Glock 17. The standard capacity for an AR-15 rifle is 30 rounds, so a 40-round magazine is a high-capacity magazine for an AR-15.

On the other hand, bans on “high-capacity” magazines typically do not consider a firearm’s standard capacity when establishing legal standards. Instead, these laws establish an across-the-board maximum (typically 10 rounds) that cannot be lawfully exceeded. Under such laws, guns that were originally designed to have a standard capacity in excess of the legislated maximum must use shorter magazines or, in the case of pistols, magazines that have been partially plugged to prevent them from being loaded to capacity.

The thinking behind such bans is that in an active-shooter scenario, the shooter’s constant need to reload will slow the assault, thereby allowing would-be victims to either flee or fight back. Supporters of such bans point to the 2011 Tucson shooting in which the shooting spree was cut short after the gunman dropped his second magazine while trying to reload, allowing bystanders crouched near his feet to grab the magazine and wrestle him to the ground.

Opponents of such bans point out that the Tucson shooting represents an anomaly (a shooter carrying only one extra magazine and dropping it) within an even greater anomaly (one’s odds of being involved in this type of mass shooting are about the same as one’s odds of being struck by lightning) and argue that survivors of other mass shootings have reported that their assailants reloaded too quickly for anyone to flee or fight.

It’s worth noting that the Tucson shooter used a true high-capacity handgun magazine that holds 33-rounds and extends well below the grip of the pistol. The long, heavy, unwieldy nature of this type of magazine may have contributed to the shooter’s dropping it. And if he’d been carrying multiple ten-round magazines, dropping one magazine wouldn’t have ended his shooting spree.

Likewise, during the 2012 Aurora, Colorado, theater shooting, the gunman’s use of a true high-capacity AR-15 drum magazine—a 100-round magazine notorious for jamming—may have prevented greater loss of life. The rifle reportedly jammed after firing only 65 rounds, forcing the shooter to retreat.

During the December 14, 2012, Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, the gunman reportedly changed magazines more often than necessary, indicating that he did not perceive himself to be vulnerable while reloading. According to The Hartford Courant, “[The gunman] changed magazines frequently as he fired his way through the first-grade classrooms of Lauren Rousseau and Victoria Soto, sometimes shooting as few as 15 shots from a 30-round magazine.”

In this video, a survivor of the 1991 Luby’s Massacre describes that assault and explains how the shooter reloaded too quickly for anyone to react:

In this video, two firearms instructors demonstrate how little a reload does to slow a shooter:

The 2007 Norris Hall massacre at Virginia Tech (the worst mass shooting in modern U.S. history prior to the June 12, 2016, shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida, and still the worst school shooting in U.S. history) lasted 11 minutes. During that time, the gunman—using a pair of handguns equipped with 15-round magazines—fired 174 rounds, killing 30 people (not counting two students killed earlier that day) and wounding 17 others. If he completely emptied each magazine before loading a full one, and if his average reload time was three seconds (very easy to accomplish), he reloaded 11 times, accounting for just 33 seconds of the 11-minute shooting spree. The use of 10-round magazines instead of 15-round magazines would have increased his total shooting time by just 18 seconds. The use of 30-round magazines instead of 15-round magazines would have decreased his total shooting time by just 18 seconds. Neither adjustment to the size of the killer’s magazines would have significantly altered the amount of time he had to target victims.

In THIS article and THIS article, survivors of the Norris Hall shooting recount that the gunman took only a second to reload.

In its final report, the nonpartisan Virginia Tech Review Panel wrote:

The panel also considered whether the previous federal Assault Weapons Act of 1994 that banned 15-round magazines would have made a difference in the April 16 incidents. The law lapsed after 10 years, in October 2004, and had banned clips or magazines with over 10 rounds. The panel concluded that 10-round magazines that were legal [under the ban] would have not made much difference in the incident. Even [revolvers] with rapid loaders could have been about as deadly in this situation. (p. 74)

This video shows just how quickly a shooter with a revolver can fire six shots, reload, and fire six more:

He fires the first six rounds at four times the top speed at which most people can fire an “assault weapon.” Even with the reload, he fires 12 rounds at twice the top speed at which most people can fire an “assault weapon” (without a reload).

Aren’t “assault-style” rifles more dangerous than handguns?

The semiautomatic rifles that gun control activists describe as “assault-style” or “military-style” (two monikers that, like “assault weapon,” refer to the appearance rather than the function of the firearm) are functionally no different from the semiautomatic handguns that are so ubiquitous in American society—both have the same rate of fire, firing one round each time the trigger is pulled.

In a typical active-shooter scenario (the focus of most proposed bans on “assault weapons”), the main advantage a shooter gains from using a rifle instead of a handgun is that a rifle is more accurate, even at relatively close range. The previously mentioned Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) study found that the minority of active shooters who use semiautomatic rifles do hit more of their intended targets; however, this increased accuracy is almost certainly the result of using a rifle (any rifle), not specifically a semiautomatic rifle or an “assault weapon.” The longer sight radius and heavier weight of a rifle make it easier to shoot accurately.

Rifles fire larger, more powerful cartridges and have greater muzzle energy than handguns; however, as shown in the video above, even revolvers, which function on a different mechanical principle than semiautomatic firearms, can match the rate of fire of a semiautomatic “assault weapon.” And as found by the BWH study, a more powerful cartridge and greater muzzle energy doesn’t necessarily translate into greater lethality in an active-shooter scenario.

Furthermore, because handgun ammunition is smaller and lighter than rifle ammunition, an active shooter can carry significantly more handgun ammunition than rifle ammunition. When you consider the BWH study’s finding that handgun rounds are just as deadly as rifle rounds in active-shooter scenarios, the fact that handguns are more easily concealable than are rifles, the fact that semiautomatic handguns can be reloaded more quickly than can semiautomatic rifles, and the fact that a shooter using a handgun can carry more rounds of ammunition than can a shooter carrying a rifle, a semiautomatic handgun offers an active shooter operating within the close quarters of a school or office building several tactical advantages over a semiautomatic rifle.

Perhaps that’s why approximately 90% of all gun homicides and the majority of mass shootings (regardless of how “mass shooting” is defined) are committed with handguns.

Aren’t “assault-style” rifles better suited than other styles of long gun for carrying out mass shootings?

As previously explained, the rifles described as “military-style assault weapons” are functionally identical to semiautomatic hunting rifles with detachable magazines. However, semiautomatic rifles are not the only long guns capable of rapid and/or sustained fire.

A high rate of fire is also possible with a lever-action or pump-action rifle or shotgun, two non-semiautomatic designs that predate the American Civil War. There are even lever-action and pump-action variants of the AR-15.

Unlike those lever- and pump-action AR variants, most lever-action and pump-action firearms do not use detachable box magazines; however, their attached tubular magazines do allow a shooter to reload without first removing unchambered rounds from the gun (as is the case with detachable magazines) and without temporarily disabling the gun by opening the breach (as is the case with integral box magazines).

This allows rounds to be added during a lull in shooting, without inhibiting the shooter’s ability to immediately resume shooting. Because of this, an assailant practiced at adding rounds before his or her gun “runs dry” isn’t vulnerable while reloading (i.e., there is never an opportunity for a bystander or potential victim to rush and disarm the assailant, because the assailant always has a loaded, operational firearm in hand).

Because the Brigham and Women’s Hospital study listed semiautomatic rifles in one category and lumped all other types of firearms together in a second category, the study is not useful for comparing the effectiveness of semiautomatic rifles to that of any other specific category of firearm, such as lever-action and/or pump-action rifles, which have comparable accuracy and muzzle velocity but a slightly slower rate of fire, or semiautomatic handguns, which have a comparable rate of fire but slightly lower accuracy and muzzle velocity.

Furthermore, the study mistakenly claims that semiautomatic rifles were banned in the U.S. from 1994 to 2004, despite the fact that the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban” only banned the manufacture of a small subset of semiautomatic rifles. The Scientific American report on the study notes:

[Philip Cook, a professor at the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University who was not involved with the JAMA paper,] believes the new BWH work has limited policy applications, because it looks at all semiautomatic rifles—instead of limiting the study to “assault weapons” as defined in the 1994 legislation. From a policy perspective, he says, “The possibility of banning all semiautomatic rifles is nil, since they are such a common type of rifle.”

These two videos show just how rapidly a lever-action rifle or pump-action shotgun can be used to engage targets (NOTE: neither of these guns are semiautomatic, and neither was classified as an “assault weapon” by the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban”):

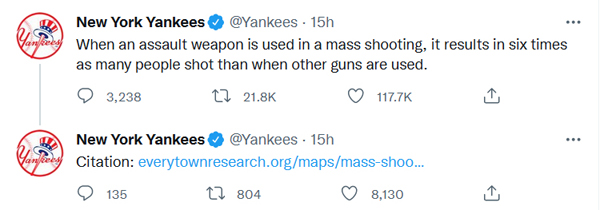

What about the claim that when “assault weapons” are used in mass shootings, six time as many people die?

This claim was promoted in a May 27, 2022, tweet by the New York Yankees:

This claim conflates mass shootings with mass-casualty active-shooter incidents. Most active-shooter incidents turn into mass shootings, but most mass shootings are not active-shooter incidents.

The majority of mass shootings are everyday crimes, such as domestic violence or gang violence, that escalate to involve at least three or four persons being wounded or killed (the exact definition of “mass shooting” varies depending on which organization is doing the counting). These everyday crimes typically involve handguns and—due to the fact that the shooter is not trying to shoot as many people as possible—result in much lower body counts.

The incidents in which “assault weapons” are used are primarily active-shooter incidents in which the shooter had time to plan the assault, is not concerned with the concealability of his or her weapon, and may be targeting victims at random and trying to shoot as many people as possible.

According to the Gun Violence Archive, America experienced 690 mass shootings in 2021 (an average of 1.89 per day), with an average of one person killed and four persons injured per incident. According to Mother Jones, America experienced six mass-casualty active-shooter incidents in 2021 (an average of one every two months), with an average of seven persons killed and three persons injured per incident.

As of January 2, 2023, the Gun Violence Archive had documented 648 U.S. mass shootings in 2022 (an average of 1.78 per day), with an average of one person killed and four persons injured per incident. Mother Jones had documented 12 mass-casualty active-shooter incidents in 2022 (an average of one a month), with an average of six persons killed and nine persons injured per incident.

When comparing death tolls, it’s important to consider the nature of the shooting. For example, where did the shooting take place? What were the ages of the persons targeted? Was the shooter targeting specific individuals or targeting people at random?

It’s much easier for an assailant to shoot a lot of people very quickly if the potential victims are crowded together on a dance floor or packed together in church pews than if they’re spread throughout a complex of offices or classrooms. Likewise, an assailant is less likely to meet resistance when assaulting elementary students (who are also less likely to flee) than when assaulting college students.

If we compare three of the four deadliest school shootings in U.S. history—the 2007 shooting at Virginia Tech University in Blacksburg, Virginia (the deadliest); the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut (the second deadliest); and the 2018 shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida (the fourth deadliest)—we get a useful comparison. (The third-deadliest school shooting in U.S. history, the 2022 shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, is not included in this comparison because the bafflingly slow response from police, which took 77 minutes to enter the classroom, makes it impossible to accurately calculate the speed with which the gunman shot and/or killed victims.)

The shooter at Virginia Tech used a pair of standard semiautomatic handguns (his primary weapon was a 9mm Glock 19; however, he also carried a Walther P22 chambered in .22 Long Rifle, as a backup) to fire 174 rounds in approximately 11 minutes, killing 30 college students and faculty (not counting two students killed earlier in the day) and wounding 17 others.

The shooter at Sandy Hook used an “assault-style” rifle (a Bushmaster XM15-E2S chambered in .223/5.56) to fire 154 rounds in approximately five minutes, killing 26 elementary students and faculty (not counting the shooter’s mother killed earlier that day) and wounding two others.

The shooter at Stoneman Douglas used an “assault-style” rifle (a Smith & Wesson M&P15 Sport II chambered in .223/5.56) to fire 139 rounds in approximately six and a half minutes, killing 17 high school students and faculty and wounding 17 others.

That means the Virginia Tech shooter fired a round approximately every four seconds, and a college student or faculty was wounded or killed for approximately every 14 seconds of the attack. The Sandy Hook shooter fired a round approximately every two seconds, and an elementary student or faculty was wounded or killed for approximately every 11 seconds of the attack. And the Stoneman Douglas shooter fired a round approximately every three seconds, and a high school student or faculty was wounded or killed for approximately every 11.5 seconds of the attack.

The Virginia Tech shooter killed one adult for every 5.8 rounds fired. The Sandy Hook shooter killed one child or adult for every 5.9 rounds fired. And the Stoneman Douglas shooter killed one adolescent or adult for every 8.2 rounds fired.

The Virginia Tech shooter’s handguns were at least as deadly as the other two shooters’ “assault-style” rifles, and none of these shooters maintained a high rate of fire (a rate of one round every two to four seconds can be matched by virtually any repeating firearm from the past 150 years).

How often are “assault-style” rifles used to commit violent crimes in the U.S?

Rifles of any kind (not just “assault weapons”) are used in approximately 4.3% of all U.S. gun homicides and a small fraction of U.S. mass shootings (regardless of how “mass shooting” is defined).

From 1982 through 2022, “assault weapons” (including “assault-style” pistols) were used in approximately one-third of mass-casualty active-shooter incidents (the types of mass shootings that make national news).

From 2004 through 2022, the U.S. averaged 5.42 annual mass-casualty active-shooter incidents, which averaged eight fatalities and 12 injuries per incident. Approximately 39% involved “assault weapons” (including “assault-style” pistols), whereas approximately 48% involved standard handguns alone.

From 2015 to 2019, rifles of any kind (not just “assault-style” rifles) were used to commit an average of approximately 441 homicides per year (an average of 3% of all homicides). That’s just over 1% of the 38,826 annual gun deaths that America averaged during that time. By comparison, as many people were murdered with blunt objects, one and a half times as many people were beaten to death with bare hands, and three and a half times as many people were murdered with knives or sharp objects.

Before the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban” went into effect, “assault weapons” were used in approximately 2% of all gun crimes.

The National Institute of Justice’s 2003 review of the 1994 “Federal Assault Weapons Ban” noted, “AWs were rarely used in gun crimes even before the ban.”

Is this confusion over “assault weapons” purely accidental, or is there a deliberate effort to mislead the public?

A 1988 study by the Violence Policy Center, then one of the nation’s leading gun control advocacy groups, unabashedly celebrates the public’s confusion over the difference between “assault weapons” and military machine guns.

The study concludes:

Assault weapons—just like armor-piercing bullets, machine guns, and plastic firearms—are a new topic. The weapons’ menacing looks, coupled with the public’s confusion over fully automatic machine guns versus semi-automatic assault weapons—anything that looks like a machine gun is assumed to be a machine gun—can only increase the chance of public support for restrictions on these weapons.

In an October 27, 2007, interview on National Public Radio, then-Miami Police Chief John Timoney—an outspoken proponent of “assault weapons” bans—was asked about that year’s increase in fatal shootings of police officers.

The reporter opened the interview by explaining to the audience that police shootings were up from 2006. She then asked Chief Timoney, “What are some of the reasons that you think this might be the case?”

Chief Timoney responded, “On quite a few of these shootings, not just automatic weapons but assault rifles have been used.”

A few seconds later, the reporter asked, “Is the kind of weaponry that criminals are able to acquire growing more powerful?”

Chief Timoney answered, “Oh, without a doubt. The federal assault weapon ban that went into effect ten years ago sunsetted about a year and a half ago—two years ago. And certainly in South Florida we’re seeing the markets here being flooded by these assault rifles. There are so many of them on the market it’s driving down the prices so that you can get these weapons for under $300. They’re much more powerful in the bullet themselves, and then there’s more of them, so instead of a ten-shooter, you now have 30 rounds.”

After a few more seconds of conversation, the reporter said, “You’re suggesting greater gun controls, it sounds like.”

Chief Timoney replied, “Absolutely! Listen, I’m fully aware of, cognizant of, supportive off the Second Amendment, but there’s no way anybody can convince me that an ordinary citizen should be walking around the streets of our cities carrying a military assault weapon.”

During this four-and-a-half-minute interview about 2007’s unusually high number of police shootings, Chief Timoney spoke of little except the dangers police officers face from “assault weapons” (which he intermittently referred to as “assault rifles” and erroneously claimed are “much more powerful in the bullet themselves”). This is particularly shocking because, according to a January 14, 2008, article published in Chief Timoney’s hometown paper, the Miami Herald, only one U.S. police officer was fatally shot with an “assault weapon” in 2007.

An August 23, 2014, article in the Miami Herald attributes a similar claim to Miami police:

Miami police say they consider the spike in shootings this year an “outlier.” They say major crime numbers remain low overall and put much of the blame on the end of the federal Assault Weapons Ban in 2004. Automatic gunfire from easy-to-get guns can spray hundreds of bullets in the blink of an eye.

In reality, rifles (of any kind) were used in only about 327 U.S. homicides in 2014, a five-year low. And as previously mentioned, “assault weapons” are not automatic weapons and cannot “spray hundreds of bullets in the blink of an eye.”

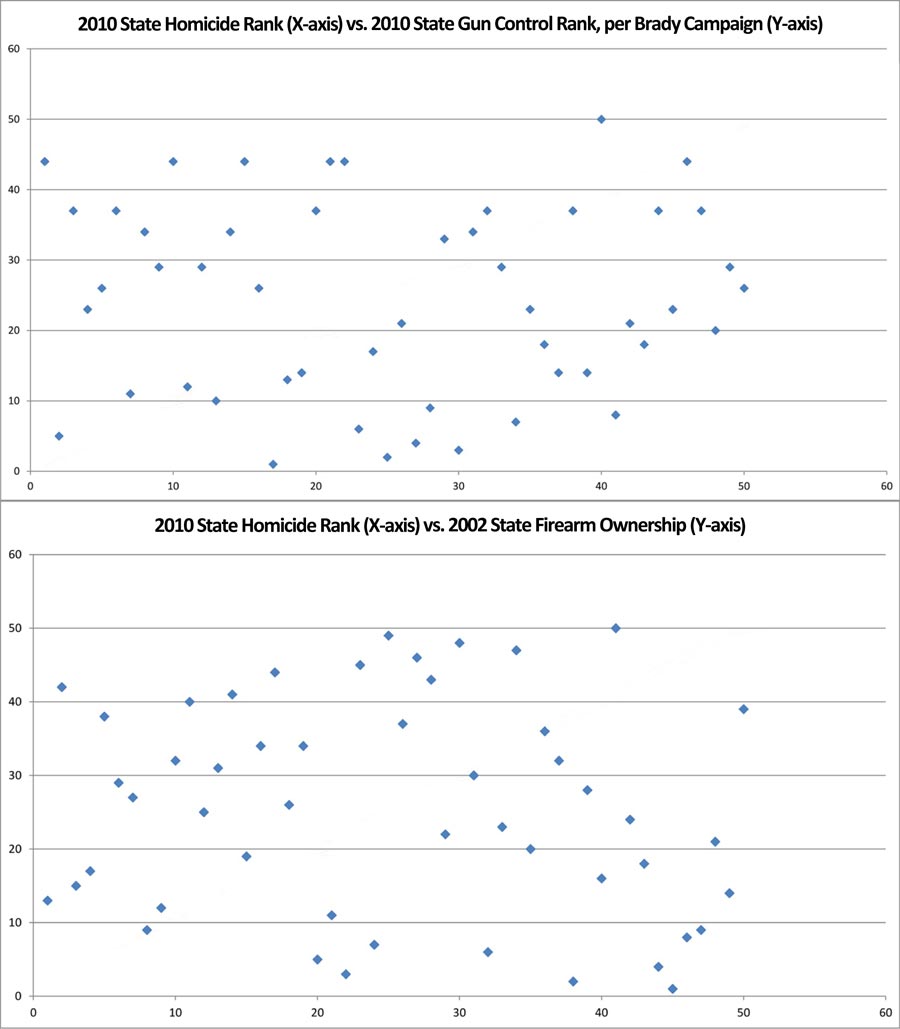

What about U.S. states that already have strict bans on “assault weapons”?

It’s difficult to distinguish between the effects of a state-level ban on “assault weapons” and the effects of other state-level efforts to reduce violent crime. However, it’s worth noting that there has historically been no correlation between the stringency of a state’s gun control laws and that state’s homicide rate. Likewise, there has been no correlation between a state’s rate of gun ownership and that state’s homicide rate.

Sources listed HERE.

It’s difficult if not impossible to analyze these types of state-level laws without first controlling for other factors such as population density, socioeconomic diversity, etc. Even then, it can be difficult to discern the effectiveness of such laws.

For example, California and Texas would seem to offer a strong comparison of the effectiveness of state-level gun laws. These are the two most populated U.S. states, each contains three of the nation’s 10 largest cities, and both are coastal border states with diverse populaces. However, each has drastically different gun laws.

The Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence ranks Texas’s “gun safety strength rank” as number 36 out of 50 and California’s as number one out of 50. According to StateFirearmLaws.org, Texas has 18 gun control laws, and California has 107.

However, year after year, the homicide rates in California and Texas are virtually identical.

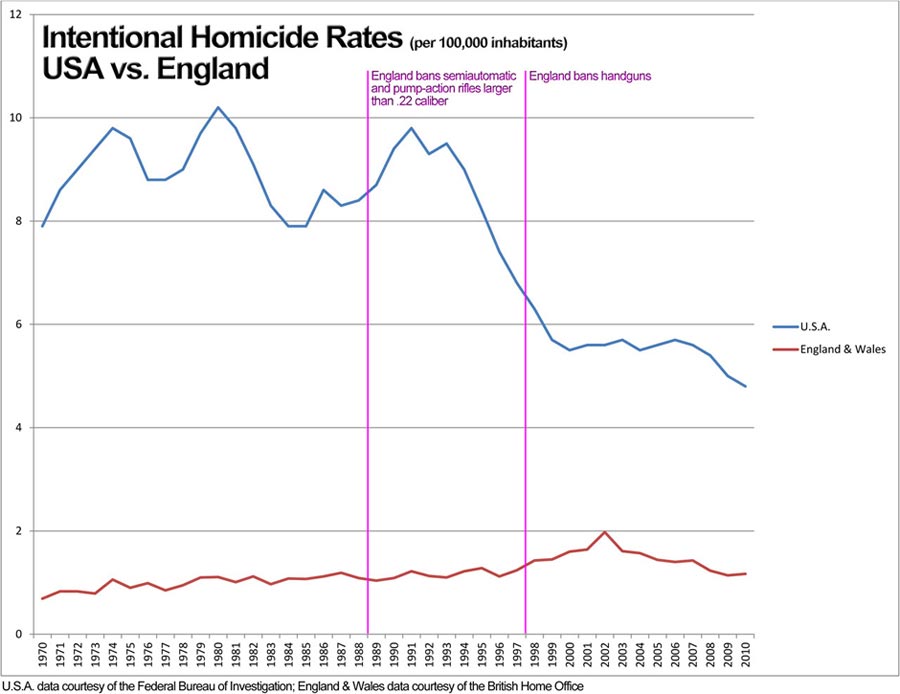

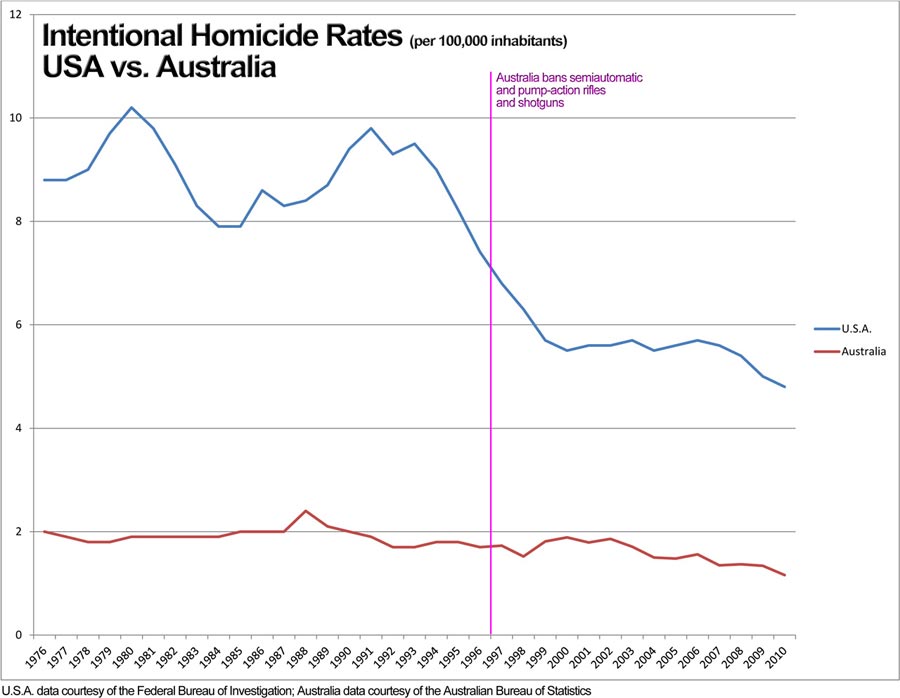

What about the claim that bans on “assault weapons” have made England and Australia much safer?

Proponents of “assault weapons” bans often speak of the great disparity between the number of gun deaths in the U.S., where “assault weapons” are legal, and the number of gun deaths in England and Australia, where “assault weapons” are banned. Comparing total numbers of gun deaths, rather than overall homicide or violent-crime rates, is an act of statistical gamesmanship designed to make such bans appear more effective than they actually are.

The U.S. population is 5.5 times that of England and Wales combined and 13.5 times that of Australia; therefore, the total number of crimes in any category is likely to be much higher in the U.S. than in England or Australia. More scrupulous advocates for banning “assault weapons” sometimes focus instead on gun-death rates, but that still ignores the question of whether such bans actually make the population safer.

A simple comparison of U.S. and foreign gun-death rates includes U.S. suicides by gun (which are 1.33 times as common as American homicides—by any means—and which, depending on the year, comprise as much as two-thirds of all U.S. gun deaths) and excludes foreign homicides committed with weapons other than firearms (if a person plotting murder in Australia can’t find a gun but still manages to carry out the crime with a knife or a club, it’s difficult to argue that Australia’s ban on “assault weapons” made the deceased victim safer).

To accurately gauge the safety of a nation, one must look at the overall homicide and violent-crime rates. Unfortunately, differences in the way the United States, Australia, and England/Wales collect crime data make it virtually impossible to precisely compare overall violent-crime rates. However, it is possible to compare homicide rates.

It’s true that the U.S. has a significantly higher homicide rate than either England or Australia; however, the U.S. homicide rate declined significantly between 1990 and 2010, whereas the homicide rates in both England and Australia remained—despite the “assault weapons” bans those countries implemented in the 1980s and 1990s, respectively—fairly constant from 1970 to 2010. The reality is that the disparity between the U.S. homicide rate and the English and Australian homicide rates was actually greater before England and Australia banned “assault weapons.”

It should also be noted that countries like Switzerland and the Czech Republic do not ban “assault weapons” or other semiautomatic firearms—though they do implement strict training, testing, and licensing requirements—and have even lower homicide rates than either England or Australia.

The media sometimes has trouble understanding that the great disparities between the U.S. homicide rate and the homicide rates in England and Australia do not correlate with the enactment of England’s and Australia’s bans on “assault weapons.”

The headline for an August 25, 2015, article from the online magazine Vox proclaims, “Australia confiscated 650,000 guns. Murders and suicides plummeted.” However, a review of Vox’s own sources suggests that Australia’s buyback program resulted in a decrease in the rate of gun-related homicides but no significant decrease in the overall homicide rate. The primary source cited by Vox addresses only Australia’s “firearm homicide rate.” A second study cited by Vox states, “The total homicide rate [had] been slowly declining throughout the 1990s (figure 4-1). In the five years post-[buyback] there [was] no pronounced acceleration of that decline.”

By erroneously insinuating that England’s and Australia’s low homicide rates are a result of those countries’ strict bans on “assault weapons,” misleading headlines and articles such as this perpetuate the myth that such weapons are the root of America’s gun-violence problem.

Even the claim that Australia’s ban on “assault weapons” resulted in a marked decrease in gun-related homicides is suspect. A peer-reviewed study published in the June 2018 edition of the Journal of Experimental Criminology notes that previous efforts to examine the ban’s effect on intentional gun-death rates had failed to adequately account for the fact that gun-related homicides were declining worldwide when the ban was implemented and that the law banning and mandating the return of semiautomatic and pump-action rifles and shotguns was only one part of Australia’s multi-year gun control strategy, which also placed stringent new restrictions on the ownership of other types of firearms, including handguns (the type of firearm used in the vast majority of U.S. gun crimes).

Prior to the study’s publication, authors Benjamin Ukert, PhD, and Elena Andreyeva, PhD, explained their findings in an interview with LDI Health Economist, a publication of Penn State’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics:

“This is a methodology issue,” Ukert continued. “Over the period in question, societies elsewhere, including Australia, generally became safer and experienced a downward trend in gun-related homicides. So the issue was how do we disentangle the effect of Australia’s intervention to exclude the effect of the broader downward trend. A lot of studies that looked at this didn’t account for that, so much of their evidence is actually part of the larger trend rather than the actual effect of the law.”

[…]

“Back in 1996,” Ukert said, “Australia tackled three different potential causes of firearm homicide — one focused on banning semi-and fully-automatic weapons, a second focused on regulating the ownership of other types of guns, and the third was a government buy-back program that removed large numbers of guns from within the population, thus lowering the stock of guns available to be used for some sort of homicide.”

“But the bottom line,” Ukert continued, “is that we don’t know which parts of those three different interventions were effective or not and that might mean that implementation of one might do little or nothing, or even two out of the three wouldn’t do much but it’s some combination that actually matters. That all requires more study.”

Both researchers pointed out that it was not their goal to compare Australia to the U.S. or suggest that Australia’s gun control strategies are well suited for the U.S.

“The very dissimilar cultural history and opinions about gun ownership along with the fact that ownership rights are manifested in the Constitution makes the situation in the U.S. and Australia very different,” Andreyeva said. “It was good that the Business Insider reporter mentioned that Australia is an island continent and doesn’t share a border with any other country, so there are maybe less opportunities for smuggling guns into the country. That is a really large difference from the U.S. situation here in North America.”

In other words, there is no evidence that Australia’s ban on “assault weapons” led to a decrease in that nation’s overall homicide rate and only dubious evidence that the ban led to a significant decrease in gun-related homicides.

As reported in the Los Angeles Times, a second peer-reviewed study, published on October 10, 2018, in the American Journal of Public Health, concludes, “[Australia’s ban on ‘assault weapons’] had no statistically observable additional impact on suicide or assault mortality attributable to firearms in Australia.” This study, conducted by researchers from St. Luke’s International University in Tokyo and the University of Tokyo, states:

Many claims have been made about the NFA’s far-reaching effects and its potential benefits if implemented in the United States.33 However, more detailed analysis of the law shows that it likely had a negligible effect on firearm suicides and homicides in Australia and may not have as large an effect in the United States as some gun control advocates expect. In the context of recent mass shootings in the United States, public health researchers and advocates for gun policy reform have identified a changed political environment in which real changes to gun control policy may be possible.34 There have been calls for action on the basis of evidence that can have a tangible impact on the crisis of firearms-related mortality in the United States.35

It is imperative that this political moment, which is so rare in the face of 20 years of political action to restrain real action on firearms-related mortality,7 not be squandered on a law that will have limited impact.

That same edition of the American Journal of Public Health includes yet another peer-reviewed study on Australia’s “assault weapons” ban, this one by Michael B. Siegel, MD, a professor of community health sciences at Boston University. Dr. Siegel’s study concludes:

The rate of firearm homicides in Australia is dramatically lower than that in the United States not because Australia banned semiautomatic rifles and implemented a buy-back program but because there was a greater degree of control of who had access to firearms even before passage of the NFA.

Three sets of impartial, peer-reviewed researchers agree that Australia’s ban on “assault weapons” is not the panacea gun control activists portray it as.

Could America follow England and Australia’s lead anyway?

England’s and Australia’s sweeping gun confiscations took place at times when those countries had approximately 0.5% and 1%, respectively, the total number of guns currently present in the United States. Because neither England nor Australia had a deeply ingrained gun culture, neither experienced the type of fierce resistance that would undoubtedly accompany any effort to confiscate guns in America.

Even if America somehow overcame that resistance and eliminated 90% of privately owned firearms—a much higher percentage than were confiscated in either England or Australia and hundreds of millions more guns than were confiscated in either of those countries—the remaining 10% would be 2,000% the number in pre-ban England and 1,000% the number in pre-ban Australia. The U.S. would still have enough guns to provide two to every soldier in the world’s 30 largest standing armies.

In short, ordering Americans to turn in their “assault weapons” would be firearm confiscation on an unprecedented scale, not a paint-by-numbers repeat of what was done in England and Australia. Resistance would be extremely high, and any benefit would likely be minimal at best.

###

For a simplified tutorial on “assault weapons,” view the slideshow at AssaultWeapon.info.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

The New York Times – Sept. 12, 2014 – NEWS ARTICLE – “The Assault Weapon Myth”: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/14/sunday-review/the-assault-weapon-myth.html

Los Angeles Times – Dec. 11, 2015 – OP-ED BY ADAM WINKLER – “Why banning assault rifles won’t reduce gun violence”: https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-winkler-folly-of-assault-weapon-ban-20151211-story.html

The Washington Post – Dec. 16, 2015 – WEEKLY COLUMN – “Why are gun rights supporters worried about bans on so-called assault weapons?”: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2015/12/16/why-are-gun-rights-supporters-worried-about-bans-on-so-called-assault-weapons-bans

The Washington Post – June 16, 2016 – NEWS ARTICLE – “Why banning AR-15s and other assault weapons won’t stop mass shootings”: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/local/wp/2016/06/16/why-banning-ar-15s-and-other-assault-weapons-wont-stop-mass-shootings

Politico – June 16, 2016 – NEWS ARTICLE – “Why Democrats aren’t pushing an assault weapons ban: And leading gun control groups don’t think they should, either”: https://www.politico.com/story/2016/06/gun-control-second-amendment-orlando-shooting-224461

New York Post – June 21, 2016 – WEEKLY COLUMN – “Why banning ‘assault weapons’ is nothing but symbolism”: https://nypost.com/2016/06/21/why-banning-assault-weapons-is-nothing-but-symbolism/

The Washington Times – Feb. 8, 2023 – OP-ED – “President Biden’s ideas on guns need to evolve” – https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2023/feb/8/president-bidens-ideas-guns-need-evolve/

Houston Chronicle – May 19, 2023 – OP-ED – “Banning AR-15s won’t work. Here’s what will.” – https://www.houstonchronicle.com/opinion/outlook/article/ar-15-ban-mass-shooting-18107185.php

MORE ARTICLES AVAILABLE ON OUR FACEBOOK PAGE: https://www.facebook.com/assaultweapontruth/